Image - Altaf Shah

Housing supply measures are in vogue, but they can’t solve the housing crisis alone.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ll have heard about the UK’s housing crisis. It’s received regular news coverage in recent years and is often a major talking point for politicians. However, that message doesn’t seem to be cutting through to everyone; out of curiosity I happened to read my ResidentsAssociation’s newsletter that had been posted through my door. Inside was a whole section dedicated to ‘Planning and Licensing’ in which its objections to local planning applications for housebuilding were detailed. How dare these councillors – who probably own their own houses – pull up the ladder behind them? According to the BBC’s housing tracker, my local area has built only 281 homes per year between 2021 and 2024, just 21% of the government target.

This is part of a wider issue across the UK – the National Audit Office identified in 2019 that only 50% of local authorities were meeting their housebuilding targets. With housing now the most expensive it has been in nearly 150 years, the backlash against NIMBYism (not in my back yard) has grown. This countermovement, known as YIMBYism (yes in my back yard) has been adopted across party lines and is the driving philosophy behind Labour’s ambitious 1.5m housebuilding target by 2029. HousingMinister Angela Rayner is leading the charge, upholding the government’s pledge to “back the builders not blockers” by intervening in local planning applications.

The idea is simple. The UK hasn’t built enough housing in decades, leading to far fewer homes per person than our European neighbours and skyrocketing prices. To bring them down again, we must build more houses. Many more. And anyone standing in the way of this building is a - pejoratively named – NIMBY. This image of too much demand and not enough supply is an intuitive one accepted across the political divide. For the centre, reforming the planning system is the key to enabling private-sector housebuilding and dulling the influence of NIMBYs over development. The left are keen to point out that large-scale construction of social housing has always been the answer to building enough supply. And on the demand-side of the equation, many on the right argue that immigration has exacerbated the housing crisis.

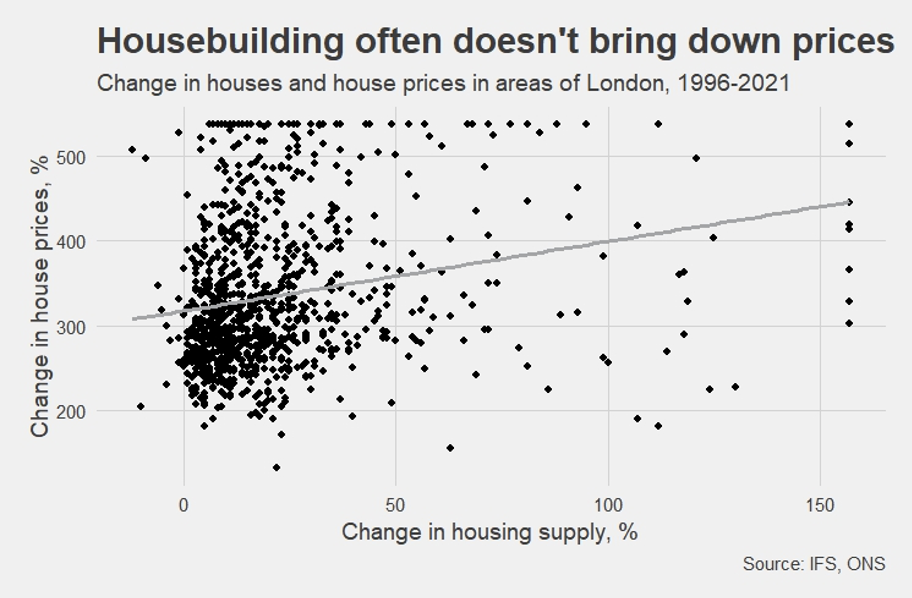

However, it isn’t always quite this simple. In fact, price falls often don’t materialise when houses are built. Looking at data from the Institute for Fiscal Studies, rates of housebuilding in London aren’t really linked to house prices (an R2 of 0.05 for any data nerds) – even less with England as a whole. You could argue that our rate of housebuilding is so pitifully low that it has made no tangible difference to house prices. A decade of low interest rates and the government driving up demand even further may outweigh any effect housebuilding has had as well. However, government forecasts only solidify the pitfalls of housebuilding alone to solve the housing crisis. Projections by the Office for Budget Responsibility of Labour’s planning reforms estimate that they would deliver 1.3m homes by 2029 but only bring down prices by 0.9%.

Let’s be clear – this isn’t a debunking of YIMBYism or an excuse to block building. The evidence in London may not support it, but the OBR projections demonstrate how building has some effect on prices. And again, there is no question that we are in a housing shortage – housebuilding may take a long time to even begin to have an effect. What is becoming apparent though is that building is only a tool in a much larger toolbox to solving the housing crisis. To start making progress, a more diverse range of policies must be considered rather than simply just the ‘build baby build’ approach taken by many among the YIMBY crowd.

Part of the reason housing doesn’t quite fit the supply and demand model is because it isn’t just bought to live in but is also bought as an investment. A report by the Bank of England in 2019 suggested that a huge chunk of the rise in house prices since 2000 has been a result of interest rates, and not housing scarcity. If house prices are driven by financial, not material, pressures then the key to bringing them down won’t be just building more. Suggestions are diverse, but they include giving local authorities greater influence over who owns houses and a change of financial policy when speculative investors buy property. We still need to build, but we need to make sure that new houses aren’t just snapped up by investors.

The structure of the development industry is another piece of the puzzle. Large-volume housebuilders (who build thousands of houses a year) build a huge proportion of new houses in the UK and therefore have a lot of influence over prices. It isn’t in their financial incentive to flood the market with new houses, so they often limit supply to keep prices higher, making large profits in the process. In fact, the market is under investigation by the Competition and Markets Authority for anti-competitive practices. Again, potential solutions are diverse. The CMA’s suggestions include a common YIMBY argument to liberalise the planning system – this and diversifying the housebuilding market have already been undertaken by government. Crucially though, the delivery of affordable housing by local authorities is an effective counterbalance to building motivated by profit – efforts are ongoing, but should be further supported.

And finally, conversations about housing often come back to tax. There are an endless number of arguments, but the most infamous is probably stamp duty, paid when a new house is bought. Many argue that stamp duty penalises older people for down-sizing, ‘gumming up’ the housing market and making housing for younger families inaccessible. Council tax also receives its fair share of criticism since it is outdated and can be more expensive for less valuable property. One suggestion is to replace both with an annual proportional property tax charged based on the value of the house. This would be both fairer than council tax and incentivise people to down-size when they need to. Proposals to penalise multiple-property ownership are often made as well.

This is by no means an exhaustive list of what is needed to solve the housing crisis, or an argument that we need to build fewer homes. Simply, if we want to making housing affordable again and get young people on the housing ladder, then the narrow-minded YIMBY approach taken by many – both in and out of government - needs to change.